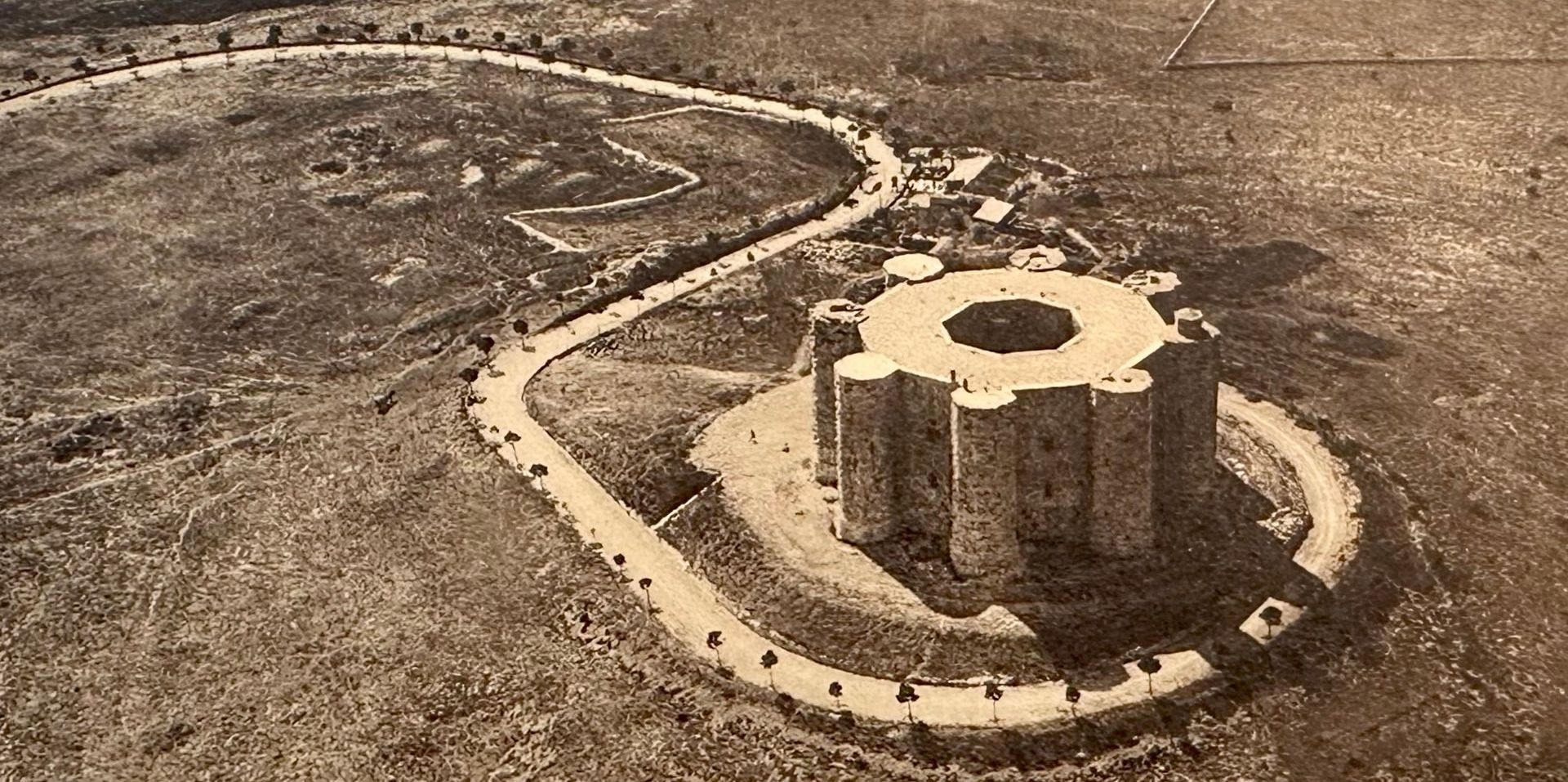

Castel del Monte:

icon of the ideal state, temple of the immortal soul

(Benedikt Nikolaus Mancini)

Photo: anonymous, 1878, historical postcard from the early 20th century; privately owned

Translated with the help of Deepl

Castel del Monte, an outstanding symbol of castle construction in the High Middle Ages, exudes an unbroken fascination, even though the intention and function of the building have remained a mystery to this day. As fortificatory as Castel del Monte may appear at first glance, the architecture hardly fulfils the requirements of a fortified building, and certainly not according to the standards of southern Italian castle building, which came from the Norman tradition, or even the particularly progressive French castle building. All other building typologies to be considered - such as palace construction, hunting lodge or pleasure palace architecture - also fail to find sufficient correspondences. Researchers agree that it is a completely unique building that cannot be satisfactorily categorised in any period-specific category, although various influences of ancient, Islamic, Romanesque and Gothic styles can be traced. The harmonious synthesis of such styles, which at the same time produces something new, is in the tradition of the syncretic Norman architectural style in southern Italy, but goes beyond this and has been recognised by prominent art historians since Georg Dehio as an expression of a short but intensive phase of the Proto-Renaissance in Apulia. Researchers also largely agree that the many special features that make Castel del Monte unique are linked to the personality of its builder, the last Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick II (1194-1250). Stefania Mola speaks of a ‘Frederician classicism’ (1).

Frederick II is challenged to defend the Kingdom of Sicily, which in his time encompasses both the island of Sicily and the territory of the later Kingdom of Naples, against many hostilities. After the death of his father, Emperor Henry VI (+1197), his mother, the Norman Constance of Sicily, had him crowned king at the age of three (1198). Shortly after this coronation, Constance also died, leaving her son, not yet four years old, an orphan. Not only was the crown of the Kingdom of Sicily now subject to years of power struggles, but the German crown also became the subject of dispute, as the election of Frederick II as Roman-German king, which had already taken place, lost its effectiveness in the face of harsh reality. For around a decade, the dispute over the German throne - between Philip of Swabia and Otto IV - shook up the situation. After the death of Philip of Swabia (1208), Otto IV was crowned emperor in Rome in 1209. Contrary to promises to the contrary, he set off on a military campaign immediately after the imperial coronation to conquer the Kingdom of Sicily, the mainland of which he gradually brought under his control. Frederick II narrowly escaped the threat of complete defeat, as some of the German princes elected him ‘other emperor’ (alium imperatorum) in 1211 and Otto IV was forced to return to Germany. However, it was not until years later that Frederick II, also with the help of the French king (Battle of Bouvines 1214), succeeded in asserting himself, being crowned in Aachen (1215) and gaining the imperial crown (1220).

Some time later (1229), Frederick II was forced to end his peaceful crusade in Jerusalem without being able to finalise matters in the Holy Land and hastily return to Italy, as papal troops had occupied large parts of the Kingdom of Sicily. Pope Gregory IX had not only banished Frederick II, but also denied him kingship. Although Frederick II managed to prevail in these conflicts, there was a need to steadily strengthen the fortifications of the Kingdom of Sicily as the most important power base of his rule.

This expansion was not only in military terms. Through a comprehensive administrative reform and a far-reaching legal reform (Constitutions of Melfi 1231), the founding of the University of Naples (1224), the relocation of the residence from Palermo to Foggia (Apulia) and other measures, Frederick II attempted to mould the Kingdom of Sicily into a kind of model state. He promoted the arts and scientific disciplines, gathering at his court ‘viri docti’, a scholarly community of around 200 people who were also tasked with translating, analysing and commenting on important ancient and Islamic sources. Frederick II personally researched the bird world of southern Italy with the support of a large number of falconers and wrote a standard scientific work, his ‘Falcon Book’ (De arte venandi cum avibus), whose empirical research quality remained unrivalled for centuries. (2) Beyond his own subject area, Frederick II consulted the scholars at his court and sent research questions to scientific centres around the Mediterranean, for example to find out about the structure of the cosmos or the nature of the human soul. Against this background, Frederick II can not only be described as a ‘researcher’ (inquisitor) and ‘lover of wisdom’ (sapientie amator), as he calls himself, but also as a scientist or natural scientist, in 13th century terminology as a philosopher or natural philosopher.

A chronicle of the 13th century says of Frederick II:

"[He] himself endeavoured to cultivate philosophy, and as he himself cultivated it, so he also ordered it to be spread throughout his realm. [...] The emperor himself, however, had schools of the liberal arts and every proven science established in his realm. [...] He attracted scholars from all countries of the world through the generosity of his gifts, and paid them as well as the destitute students a fixed salary, so that people of every class and wealth would not be deterred from the study of philosophy due to any lack."(3)

It is obvious, and indeed obvious, to link the two spheres to which Frederick II attached so much importance: Architecture and philosophy. Carl Arnold Willemsen, Heinz Götze and Stefania Mola have already postulated a multi-perspective and interdisciplinary approach that incorporates philosophical aspects in order to deal appropriately with the Castel del Monte phenomenon. In the 1980s, Heinz Götze chose a methodology that combined archaeological and art-historical findings with cultural-historical and, to some extent, philosophical concepts, an approach reminiscent of Erwin Panofsky's iconological methodology. Götze sees Castel del Monte as a building that ties in with ancient, or more precisely Augustan, traditions and, in his opinion, even represents an architectural symbol of the Pax Augusta.(4) He also recognises connections to ancient philosophy, in particular to the Platonic school.(5)

Inner courtyard Castel del Monte (Foto: Mancini)

According to the author's thesis, Castel del Monte is characterised by the geometric form of the octagon, as exemplified in Aachen (Charlemagne's court church) and Jerusalem (Dome of the Rock). The building probably represents eight dominions of royal rank (Sicily, Germany, Imperial Italy, Burgundy, Rome (limited), Jerusalem, Cyprus, Sardinia) in connection with the imperial crown. The eight octagonal towers and the large inner octagon can symbolise these ruling relationships. Taking up elements of Solomonic and ancient temple architecture as well as ancient triumphal arches (for example in the design of the main portal), the architecture appears almost as a defiant triumph against the powerful opponents of Frederick II, who was excommunicated from the church by the Pope for the second time in 1239 and became the focus of the papal crusade movement. Thematically, the building could model the concept of the ideal state as originally developed by Plato and later discussed and commented on, particularly in Islamic philosophy, to which Frederick II had access. In the 13th century, Plato's doctrine of the immortality of the soul provided the clearest answers to the study of the soul, with which Frederick II was intensively occupied. Pythagorean, Platonic and Aristotelian is also the approach to understanding mathematics and geometry as precursors of metaphysics, as was the case in the 13th century.

Main portal of Castel del Monte with triangular pediment and rectangular field (Photo: Mancini)

Arch of St Augustus in Orange with triangular pediment and rectangular field (Photo: Mancini)

The variety of interpretative approaches that Benedikt Mancini presents in his study ranges from well-established findings to speculative - but not unfounded - interpretations. In the area of speculative considerations, those on Platonic or Neoplatonic metaphysics are the most daring. However, they make it possible to integrate the many other points of view - including those aspects that have received too little attention in previous analyses of Castel del Monte: for example, the consistent analysis and symbolic interpretation of the symmetry of the centre, the main portal, the towers, the interior design, the Meleager spolia relief and the use of coral breccia, also the counting of royal dominions in connection with the imperial crown, the investigation of the building policy resonances of the ongoing conflict between the papacy and the empire (especially in the context of such buildings in Speyer, Cluny, Rome), an even more rigorous study of octagon symbolism, a greater consideration of Salian and Hohenstaufen memoria culture, a more extensive evaluation of the medieval interpretation of the Dome of the Rock as the Temple of Solomon, a more specific study of imaginative references to ancient imperial architecture, a more precise consideration of Norman artistic and architectural design, which extended beyond the Hohenstaufen tradition, including the extraordinary ability to syncretise various trends and shape them into something new.

The conflict between the emperor and the pope became increasingly dramatic after the death of Honorius III (1227). Frederick II was excommunicated twice by Gregory IX (pontificate 1227-1241), although the second excommunication has not been lifted to this day. In 1227, the dispute with the Pope was sparked by the issue of the crusades; in 1239, questions of power took centre stage (in particular the dispute over Sardinia). The pope and emperor clashed on several levels. Art and architecture are also relevant in this context, serving political goals among others.

Against this background, Castel del Monte appears as a monument and expression of imperial power, which seeks to strengthen its legitimisation in the Carolingian, Augustan and Solomonic traditions, which is also reflected in architectural-historical references. In addition to ancient buildings, the Dome of the Rock, understood as a restoration of the Temple of Solomon, San Vitale (Ravenna), Aachen Cathedral and probably also the imperial cathedrals of the Rhineland with their enormous octagonal domed towers (especially Speyer) play a special role here. Castel del Monte differs from the model buildings in question, with which it shows clear similarities on the one hand, but at the same time with its open centre and the eight mighty towers, which represent and multiply the most important architectural symbol of power of the time (in Italy), the tower.

Due to its geographical location, silhouette, structure and interior design, the building appears to be an architectural model for the ideal state as designed by Plato and as intensively discussed and commented on, particularly in Islamic philosophy, to which Frederick II had access, right up to the 13th century. In Plato's ideal state, reason and justice reign, represented by a community of philosophers (or by a monarch who is also a philosopher). Metaphysical aspects do not serve power-political goals, but rather assign the state the task of enabling souls to ascend to transcendence. According to Plato, the state, explicitly conceived as a city-state (polis), should be within easy reach of the sea, but not directly on the coast. The houses of the inhabitants should be similar and form a ring of walls.

All of this has its counterparts in Castel del Monte. Three estates form the state, the structure of which can be modelled on Castel del Monte: The inner octagon can be assigned to the philosophers (or the monarch; first estate) as their domain. The octagonal towers correspond to the guardians (second estate). The surrounding area, which is still exceptionally extensive in Castel del Monte today, would correspond to the area of the farmers, craftsmen, tradesmen and merchants (third estate). Inside the building, the similar rooms could indicate the equal status of the philosophers. The stone bench running around the upper floor (in all rooms), which seems quite unusual for medieval castle architecture, would, together with the benches in the raised window niches, refer to the Platonic dialogue situation in which two or more scholars argue in front of a group of interested people or students.

Science according to the prevailing understanding of the 13th century extends from the artes liberales via physics and mathematics to metaphysics. Castel del Monte's consistent geometry can be located in a key position in this system, in the field of mathematics, which mediates between physics and metaphysics, for example by helping to abstract observations of nature and explain them through a superordinate ontology. This leads to the philosophical, metaphysical concepts of God, the unmoved mover (Aristotle) and the good that diffuses itself (bonum diffusivum sui) (Platonic tradition). All of this is to be combined with a philosophical understanding of reality that assumes a unified origin of all being and the return to this origin. This goes hand in hand with the metaphysical determination of the relationship between the one and the many or the whole and its parts.

From an aerial perspective in particular, these concepts with regard to Castel del Monte appear to be approaches that can plausibly explain the symmetry of the centre and the diffusion of the octagon into eight other octagons and open up a deeper, almost cosmic or metaphysical meaning of the building, especially when one considers that in ancient philosophy symmetry is regarded as the epitome of beauty and order in the cosmos, a cosmos that is otherwise in danger of falling into chaos. Dante Alighieri will use precisely these concepts in the Monarchia to describe the nature and structure of ideal rule (Monarchia, I, vi, ix, xv).

Spolia relief on the north-east wall of the inner courtyard. It most likely depicts the carrying home of the dead King Meleager. (Photo: Mancini)

Marble capital above a bundle pillar, also visible is the opus reticulatum (top left), which is unusual for medieval buildings and is described by Vitruvius as a characteristic of the Augustan period. (Photo: Mancini)

The centre-symmetrical structure of Castel del Montes refers not only to political and scientific (mathematical and metaphysical) symbolism, but also to the major theme of memoria. In sepulchral and memorial architecture, centre-point symmetrical central buildings (as round buildings or polygons) predominate. This also includes the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and, in a broader sense, Aachen Cathedral and the Dome of the Rock. After Charlemagne's death, Aachen Cathedral took on the functions of a burial church and memorial church. The fact that the Aachen Court Church was one of the model buildings for Castel del Monte is undisputed among researchers, even if further research seems necessary into the details and the character of the sacred. The Dome of the Rock can also be regarded as a model building, although it should be borne in mind that in the Middle Ages the Dome of the Rock was regarded as a restoration of Solomon's Temple and the extensive temple symbolism was transferred to the Dome of the Rock. The tradition of Muhammad's ascension was only transferred to the Dome of the Rock years or decades after its construction. Older is the multi-layered tradition that associates the rock with the salvation of Noah, the sacrifice of Abraham (and the salvation of Isaac), the ‘fountain of souls’, access to the world of the dead and the gates of heaven. This tradition was subsequently combined with the theme of the ascension of Muhammad. In Islamic architecture, the Dome of the Rock became the model for tombs and memorial buildings, while Islamic mysticism saw the ascension of Muhammad as a symbol of the soul's ascent to God.

Emperor Frederick II was part of a long tradition of memoria culture, to which he personally contributed in Aachen, Speyer and Palermo. He gave only sparse instructions for himself in his will, although he had to fear that his burial and memoria could be jeopardised, especially after the church ban of 1239 (as the example of Henry IV shows, who was only buried in the tomb of Speyer Cathedral many years after his death, after the Pope had absolved him from the church ban; the excommunicated King Manfred, however, was buried in a ravine after the defeat of Benevento in 1266). Many elements of Castel del Monte refer to the theme of the soul and memoria, including the Christian, but also Islamic and ancient symbolism of the figure of eight, the shape of a central symmetrical building, the spolia relief on the north-eastern wall of the inner courtyard with the theme of the return of the dead King Meleager.

But even if the emperor did not intend it, Castel del Monte reminds us like no other building of Frederick II as a ruler who shaped a pre-modern legal and state system, brought about a proto-Renaissance in the art of Apulia and can be considered a pioneer of an empirical understanding of science. Castel del Monte, also in the tradition of Norman architecture, symbolises a growing European culture in the sense of an advanced syncretism. In the sense of medieval networking possibilities, this culture was globally orientated and still radiates this today.

Notes

(1) Mola (2011), p. 71.

(2) Houben (2008), p. 44; Stürner (2003), p. 345f.

(3) Nicolaus de Jamsilla, Historia de rebus gestis Friderici II imperatoris eiusque filiorum Conradi et Manfredi; Quellensammlung (I), p. 637f.).

(4) Götze (1986), p. 100; Götze (1991), p. 53f.

(5) Götze (1986), p. 72f.

Literature

Biller, Thomas: Die Burgen Kaiser Friedrichs II. in Süditalien. Höhepunkt staufischer Herrschaftsarchitektur, Darmstadt 2021.

Calò Mariani, Maria Stella; Casssano, Raffaelo (Ed.): Federico II. Immagine e potere, Venedig 1995.

Dante Alighieri: Convivio, Raleigh 2013 (Aonia edizioni).

Dante Alighieri: Monarchia. Lateinische/Deutsch. Studienausgabe. Einleitung, Übersetzung und Kommentar von Ruedi Imbach und Christoph Flüeler, Stuttgart 1989.

Demandt, Alexander: Der Idealstaat. Die politischen Theorien der Antike, Köln/Weimar/Wien (3) 2000.

Esch, Arnold; Kamp, Norbert (Ed.): Friedrich II. | Federico II. Tagung des Deutschen Historischen Instituts in Rom im Gedenkjahr 1994, Tübingen 1996 (Bibliothek des Deutschen Historischen Instituts in Rom Bd. 85).

Flasch, Kurt: Das philosophische Denken im Mittelalter von Augustin zu Machiavelli, Stuttgart 1986.

Görich, Knut: Die Staufer. Herrscher und Reich, München (3) 2011.

Götze, Heinz: Castel del Monte, Gestalt und Symbol der Architektur Friedrichs II., München (2) 1986.

Götze, Heinz: Die Baugeometrie von Castel del Monte. Vorgetragen am 27. April 1991, Heidelberg 1991 (Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-historische Klasse, Jg. 1991, Bericht 4).

Grebner, Gundula; Fried, Johannes (Ed.): Kulturtransfer und Hofgesellschaft im Mittelalter. Wissenskultur am sizilianischen und kastilischen Hof im 13. Jahrhundert, Frankfurt a. M. 2008 (Wissenskultur und gesellschaftlicher Wandel Bd. 15).

Houben, Hubert: Kaiser Friedrich II. (1194-1250). Herrscher, Mensch und Mythos, Stuttgart 2008.

Legler, Rolf: Das Geheimnis von Castel del Monte – Kunst und Politik im Spiegel einer staufischen „Burg“, München 2008.

Leistikow, Dankwart: Zum Mandat Kaiser Friedrichs II. von 1240 für Castel del Monte, in: Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters Bd. 50 (1994), S. 205-213.

Marongiù, Antonio: Ein „Modellstaat“ im italienischen Mittelalter: Das normannisch-staufische Reich in Sizilien, in: Wolf (Ed.), Stupor Mundi, S. 325-348.

Mola, Stefania: Castel del Monte, Bari 2011.

Panofsky, Erwin: Aufsätze zu Grundfragen der Kunstwissenschaft. Herausgegeben von Hariolf Oberer und Egon Verheyen, Berlin 1992.

Platon: Werke in acht Bänden; griechisch und deutsch. Übersetzung von Friedrich Schleiermacher (u. a.). Herausgegeben von Gunther Eigler, Darmstadt (2) 1990.

Quellensammlung (I): Kaiser Friedrich II. in Briefen und Berichten seiner Zeit. Herausgegeben und übersetzt von Klaus J. Heinisch, Darmstadt 1968.

Quellensammlung (II): Kaiser Friedrich II. Leben und Persönlichkeit in Quellen des Mittelalters. Herausgegeben von Klaus von Eickels und Tania Brüsch, Düsseldorf 2006.

Saponaro, Giorgio (Ed.): Castel del Monte, Bari 1981.

Schirmer, Wulf: Castel del Monte: Forschungsergebnisse der Jahre 1990 bis 1996 in Zusammenarbeit mit Günter Hell, Ulrike Hess, Dorothé Sack, Werner Schnuchel, Christoph Uricher und Wolfgang Zick und mit Photografien von Rafael Cardenas-Dopf, Mainz 2000 (Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. Forschungsstelle Archäologisch-baugeschichtliche Erforschung des Castel del Monte).

Stürner, Wolfgang: Friedrich II. Teil 1: Die Königsherrschaft in Sizilien und Deutschland 1194-1220, Darmstadt 2003.

Stürner, Wolfgang: Friedrich II. Teil 2: Der Kaiser 1220-1250, Darmstadt 2003.

Tavolaro, Aldo: Astronomia e Geometria nella architettura di Castel del Monte, Bari 1991.

Willemsen, Carl Arnold: Castel del Monte. Das vollendetste Baudenkmal Kaiser Friedrichs des Zweiten. Mit neunundfünfzig Bildtafeln, Frankfurt a. M. (2) 1982.

Willemsen, Carl Arnold: Castel del Monte. Die Krone Apuliens. 32 Bildtafeln, Wiesbaden 1955.

Wolf, Gunther G. (Hrsg.): Stupor Mundi. Zur Geschichte Friedrichs II. von Hohenstaufen, Darmstadt 1982.

Zanker, Paul: Augustus und die Macht der Bilder, München 1987.